by Art Cohn

Chambly is a historical power spot and after our tow by horse and Churchill, we tied Lois up in the Basin just above locks 3-2-1 as we had in 2008. We happily plugged into power that Parcs Canada had arranged and fretted over the shower we previously had access to in the Superintendants House that was not going to be available to us this time. However, our friend Claire, one of the veteran Chambly Canal lock tenders, had a portable shower she had acquired for her lock and arranged to move it to the bathhouse on the lower locks where we were staying. With the important tasks of power, bathrooms and showers taken care of we were indeed ready for action and action we had, seeing over 1100 people on a busy holiday weekend and talking history to all.

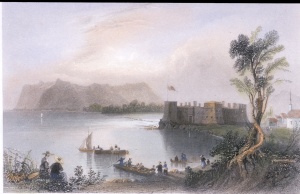

Chambly is such an important place in the story of our shared heritage. Written about by Samuel de Champlain on his quest to see a “large lake filled with beautiful islands” which he named Lake Champlain, it was first fortified by the French in the 17th century. During the first year of the American Revolution Chambly was successfully taken by Richard Montgomery during the invasion of Quebec. Later, in the attack on Quebec City during a New Years Eve snowstorm General Montgomery was killed, Benedict Arnold badly wounded and the American army demoralized. They struggled through the Quebec winter only to reach spring sick with smallpox* and witnessing British reinforcements arriving at Quebec. Forced into a hasty retreat they abandoned one position after until finally falling back to Chambly, Saint Jean then Isle aux Noix before finally being able to embark on their few warships, described more as “floating wagons” before tumbling back to Lake Champlain. Now the 1776 campaign would fall to the shipbuilders and naval teams on both sides to see who could build the strongest fleet in the fastest time in anticipation of battle.

Chambly was an essential place in this strategy. British warships from the St. Lawrence could sail to the Richelieu River and as far as Fort Chambly, but here, as Samuel de Champlain had learned in 1609, the rapids of the Richelieu presented an effective barrier to ships. However, the British had the mightiest navy in the world and a core of experienced officers and men one of whom was Lt. John Schank. The Lieutenant was a mechanical genius and he was given the responsibility of assembling a fleet capable of taking control of strategic Lake Champlain from an American force commanded now by a healed “Commodore” Benedict Arnold.

Contemplating his situation Schank struck on an ingenious solution…why not take existing warships as far as the Chambly Basin, then take them apart to their lower hulls and transfer the pieces to Saint Jean at the other end of the rapids and reassemble them? That is exactly what he did and by October the reassembled British fleet had embarked from St. Jean to seek out the Americans in what has became known as the Battle of Valcour Island.

That story is a centerpiece of LCMM’s research and has been a current focus of our recent work at the Valcour Island Research Project, an effort to systematically map the submerged battlefield. That project was stimulated by the discovery of an exploded cannon under the mud of Valcour Bay by Ed Scollon and has added much to our understanding of that important event. Our lake research has also led to the discovery of Spitfire, the last unaccounted for American gunboat from Arnold’s fleet. The Spitfire Management Project is one of the most important nautical archaeology projects in which LCMM is currently engaged. To learn more about these important projects check out our website at www.lcmm.org and visit our Basin Harbor campus.

Back to Chambly. After the American Revolution ended, Chambly once again became a center in the transportation and trade of the region. As peace prevailed and settlers streamed into the Champlain Valley log rafts from Lake Champlain were floated to Saint Jean before being floated in sections over the Richelieu rapids and then reassembled at Chambly for their final leg to Quebec City. Chambly was an active seaport with a large basin and significant trade but the friction between Great Britain and the US which led to the War of 1812 threatened all that. The Federal Embargo Act of 1808 ordered Champlain Valley residents to stop trading with British Canada. However the Embargo seemed more to empower the enterprising Champlain Valley natives who continued their northern trade by smuggling vast quantities of materials over the border, and this did not stop when formal war was declared in 1812.

During the War of 1812, the Americans, perhaps remembering the early success of their invasion of Canada in 1775, tried to invade Canada via Lake Champlain in three separate campaigns, each a failure. Finally, in 1814, British Governor General Prevost attempted to invade the United States via the Lake Champlain-Richelieu corridor supported by the large British bases of operations at Chambly, Saint Jean and Isle aux Noix. This invasion by land and sea with veteran regulars recently arrived from success over Napoleon in Europe would prove to be their undoing. The combined American army and naval success at Plattsburgh, NY, remembered today as “Macdonough’s Victory on Lake Champlain” was the finest hour for the American’s and dealt the British such a blow that the war was soon brought to a negotiated conclusion in which no territory was exchanged and no borders changed.

With the war over Chambly and the rest of the Richelieu communities settled down to resume their successful trade relationship with the Champlain Valley, but a dark cloud was on the horizon. This time the threat was not war but the potential devastating impact to this lucrative trade pattern by a plan gaining traction in New York State to build a new canal connecting Lake Champlain to the Hudson River. In 1817, the Canadian merchants worst fears were realized when the New York State legislature approved the construction of the Northern and Western canals. The completion of the Champlain canal connecting Lake Champlain to the Hudson River would potentially turn significant amount of trade that had previously followed the water north to new markets in the south, and that is just what happened.

When the new Champlain Canal opened in 1823 it was like the northern spigot of trade closed and the southern spigot was opened. The commercial world of Saint Jean, Chambly and Montreal merchants was so hard hit that despite the military objections for a canal to by-pass the Chambly rapids, lest the Americans find it easier to invade again through the Lake Champlain-Richelieu corridor, the Chambly Canal, a 12-mile system was pressed. Built in spurts over the next twenty years it was finally completed in 1843 and its completion dramatically expanded the canalers inland route options. Now the Canadian ports along the Richelieu, St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers would join Lake Champlain, the Hudson and Erie Canal options. This northern route, through Chambly, is the water highway we are following today. In fact, I am beginning this blog at the entrance to the Lachine Canal a component of the northern system first completed in 1825.

Today, it is impossible to walk through Chambly and not be taken with the depth of its multi-layered history. Our dockside location at the basin above the locks was made more interesting and easy to interpret by a 19thcentury photograph presented to us by Bernard Halle, our Parcs Canada friend, showing a canal boat loading hay in this exact location. The wonderfully restored and interpreted Fort Chambly presents the many military aspects of this strategic place and a special exhibition presents a perspective on the War of 1812.

A short stroll past the fort on the quiet street that follows the rapids in the river brings us to the home of Charles-Michel d’lumbery de Salaberry, the hero of the 1813 Battle of the Chateauguay River and a Canada’s national hero. His home, interpreted by an outdoor sign, is presently for sale.

Today the Parcs Canada restored fort and operating canal reflects on Chambly’s rich military and commercial history. The towpath that once saw teams of horses slowly towing canal boats to Saint Jean or Chambly is alive with bicycles, runners and walkers while many of the bridges and the masonry locks still operate with hand cranks and are interpreted by outdoor panels that provide the public with a reflection on this rich place with which we share so much history. Today, on special occasions, the sound of horses footsteps can still be heard as the Lois McClure gets slowly sped on her way by the same horse power that once powered the original canal boats that came before her and helped inspire her mission.

Special Thanks to:

- Parcs Canada

- Claire Chasse

- Bernard Halle

Art Cohn

Captain, C.L. Churchill

* General John Thomas and hundreds of soldiers died of smallpox during the American retreat in 1776. General Thomas is today remembered on a bronze plaque near Fort Chambly. The American soldiers buried on Isle aux Noix are remembered by a small plaque on the island.

Thank you for this article, Art!

Pingback: Chambly - Lake Champlain Life